Blog

Disrupting ‘disruption’

‘Who has the right to “disrupt” the university?’, a Jewish Currents essay by Dennis Hogan asked in May, analysing what’s at stake when students – or managment – interve in university life. This question has also been central at Utrecht University in the past months. Mia You powerfully captures the dissonances of being a good or bad daughter to the (and particularly: our) institution at a time of student encampents in solidarity with the people in Gaza and the violent police crackdowns to shut them down for Too Little Too Hard.

When Maha El Hissy and I were planning our June panel discussion “Disrupting Translation” with Thalia Ostendorf and Jon Cho-Polizzi – a collaboration with Maha’s #Vorzeichen series for the Goethe Institute and a sequel to January’s “Disrupting Literature” event – it was a central concern that the term “disruption” has itself become a staple of corporate branding in higher education and the literary world alike and is in dire need of disruption itself. We are immensely grateful to Thalia and Jon, who brought such wisdom and wit to all questions around navigating these various spheres (a recording will be avaible soon).

Around the same time, it was on full display what kind of disruptions are and are not welcomed in the British and German literary scenes, on which I focus in this project. In the UK, the Fossil Free Books collective has been highly successful in shedding light on the material entanglements between British literary festivals and investments in environmental disaster, international law abuses, and war. As a result, its organisers have been facing significant backlash, some media outlets accusing them of anonymous intimidation when they precisely leveraged their visibility as authors and workers in the book industry. I touch upon the way authors like FFB organiser Yara Rodrigues Fowler position such practical work as a necessary complement to their political writing in my most recent publication “Aktive Literatur” in Berlin Review, which thinks through Rodrigues Fowlers and Isabella Hammad’s second novels. (Apologies, here, for the exercise in self-promotion that these overview blog posts entail.) In the piece, I briefly contrast their literary approaches with that of Zadie Smith. Shortly after its appearance the contrast in their wider politics became all the more apparent as Smith published a New Yorker essay on the student protests. Rodrigues Fowler’s immediate social media comments were re-shared widely, as was Hammad response essay for the New York Review of Books.

As I have extensively written on the various “disruptions” of the German literary scene in previous blog posts, I will keep today’s short and merely point to a radio report by Lara Sielmann for Deutschlandfunk Kultur, which reflects on the public part of “Schreib (nicht) mit Gedichten die Geschichte”, a day of discussions I co-curated alongside Dima Albitar Kalaji, Maryam Aras, Asal Dardan, Maha El Hissy, Lena Gorelik, Eva von Redecker and Insa Wilke.

In the past two months, I also shared my comparative research in Leuven and Leiden, where I got to keynote the COLLAB project’s inaugural symposium Authorship in a Global and Transnational Context (“‘Good Immigrants’ Across Contexts: Authorial Collaboration In/Between/Beyond Germany”) and the OSL PhD Day Literature in Community (“Publishing in Community: Contemporary Anthologies Against Exclusionary Discourses”). These gatherings’ explicitly collaborative spirit also fuelled last week’s Artistic Residency conference at University College Dublin. Thanks to all organisers for creating these opportunities for genuine exchange.

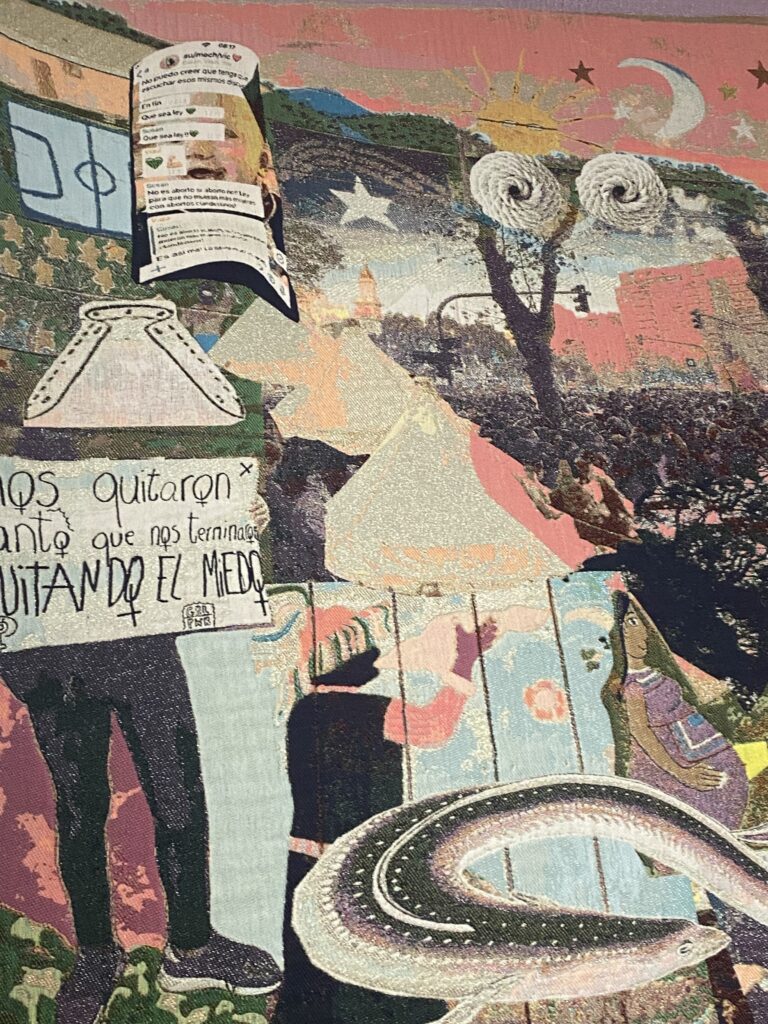

I’ll end on a photo I took in the Irish Museum of Modern Art. It shows a snippet of Mercedes Azpillicueta’s tapestry “Potatoes, Riots, and Other Imaginaries” (2021), in which the artist brings together movements – or disruptions – from Argentina to the Netherlands: